A Brief History of the NBR

The railway was initially proposed as "The Great North British Railway", but "Great" was soon dropped. The proposed line was to link Edinburgh with Berwick on Tweed. George Hudson became quite deeply involved because it fitted in with his plans for a main line between London and Edinburgh. After the Act received Royal Assent, building work commenced almost immediately and the line was opened to traffic just two years later.

Before trains started running on the main line, the NBR took over the Edinburgh & Dalkeith Railway, which was already operational (horse drawn, 4ft 6in gauge). A line which was planned between Edinburgh & Hawick received authorisation in 1845 and was taken over by the NBR that year. During the 1840/50s, railways that were later to become part of the NBR were building and taking over lesser lines. In the late 1850s, there were continuing plans for expansion. The Caledonian Railway tried to prevent the NBR extending the Hawick line to Carlisle but the NBR, rather astutely, acquired the Port Carlisle Railway which gave them access to Citadel station, and also, incidentally, a line to Silloth on the Cumberland coast. The line from Hawick to Carlisle was opened to traffic on 1862. Other acquisitions/amalgamations happening around this time was the Edinburgh, Perth & Dundee, The West of Fife and the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railways; with these additions, the NBR was transformed into a major railway company. The NBR was particularly lucky to merge with the E&GR because that line had had very close associations with the CR for some time and had nearly been taken over by that railway.

The E&GR's main station in Edinburgh was the General. The NBR's main station was Canal Street, the EP&D also had an Edinburgh terminus; in time, the General became the main station for the enlarged NBR and was re-named Waverley the other two closed.

The main station in Glasgow was Queen Street. Operating from Queen Street was a problem because of the 3/4 mile long 1 in 45 Cowlairs bank which started near the platform ends. For many years, a large winding engine was situated at Cowlairs and hauled trains up by means of a rope (and later cable). Subsequently, trains were banked up, often by 0-6-2 tanks. Some were fitted with a special slip coupling so that they could be detached without stopping the train.

The NBR was keen to gain access to Newcastle and entered discussions with the North Eastern Railway (NER); the result was the right of running powers into Newcastle via the NBR Border Counties line which ran from Riccarton junction near Hawick through sparsely populated country to Hexham and thereon to Newcastle on the NER's Newcastle Carlisle line; whereas the NER gained running powers into Waverley from Berwick and was given the mandate to handle all the East Coast mainline express traffic north of the border.

On the completion of the Midland Railway's Settle & Carlisle line, through running commenced from St Pancras to Edinburgh over the Waverley route. The coaching stock for these trains was financed jointly - M&NB Joint Stock. The joint stock was all built at Derby and was in the Midland livery.

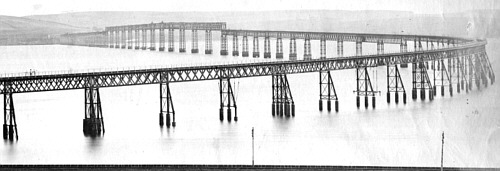

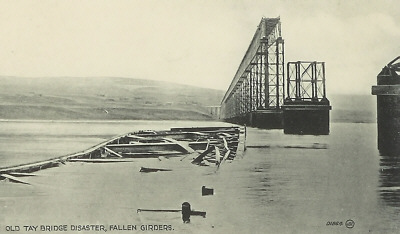

Thus by the middle of the 1860s, the NBR was running mainline trains to Berwick, but no further; to Carlisle, to Glasgow and to Aberdeen. The route to the last named destination was far from a straightforward journey as it involved passengers taking ferries across the Firths of Forth & Tay and the last 28 miles to Aberdeen were made by means of running powers from Kinnaber Junction over Caledonian Railway metals. This was clearly much less convenient than the Caledonian route from Edinburgh, s So plans were made to bridge the Tay and Forth. Thomas Bouch was appointed designer and overseer for the Tay crossing project. Both the preliminary investigations and construction were badly flawed, defects being covered up and other dubious practices perpetrated. There was no account taken of any possible effects of wind pressure on the structure. The bridge was opened by Queen Victoria in 1878; Bouch received a knighthood. On Sunday 28th December the following year, during the course of a raging storm, part of the bridge collapsed whilst a train was crossing with total loss of life of all on board - about 80 men, women and children. The Board of Inquiry investigation which followed revealed all the shortcomings and put the blame squarely on Bouch. Although Bouch did make terrible mistakes, the contractors were also badly at fault but Bouch was not aware of their shortcomings, if he had not put so much trust in them, these faults would soon have been apparent. Bouch was a broken man and died a couple of years later. Before the disaster, Bouch's design for the Forth crossing, a suspension bridge, had been accepted and work had commenced. This work was stopped immediately.

The NBR was determined to first re-cross the Tay and also bridge the Forth. The Barlows, father and son, were appointed engineers to the new Tay crossing. Great care was taken to ensure the effect of wind pressure was taken account of in both designs. The design engineers for the Forth Bridge were Fowler and Baker with the Barlows and T E Harrison as consulting engineers. The design was for a cantilever bridge, with six cantilevers in pairs on three piers.

With the completion of the Forth Bridge, the NBR had the much better routes between Edinburgh, Perth, Dundee and Aberdeen than the arch rival Caledonian Railway.

The last main expansion of the NBR came with the West Highland Line (and extension). This line was built by a separate enterprise but worked by the NBR from the start. It was later absorbed by the NBR. The West Highland commenced at Craigendoran and continued for 100 miles through wild, hilly country to Fort William. At the northern end there was a short branch to Banavie. The line was steeply graded; there were many miles with gradients between 1 in 50/60. It was single track with passing loops at most stations plus a few other passing loops. The NBR purpose built locomotives and rolling stock for the West Highland. A few years after opening the main line, the West Highland Extension was built from Banavie to Mallaig, 41 miles, (43 miles from Fort William). The contractor for the extension was McAlpines and they built some structures, notably Glenfinnan Viaduct, from concrete; this was one of the very earliest uses of this material in construction work.

In conjunction with the railway operations, the NBR had a fleet of ferries on the Clyde and also on Loch Lomond, the latter were jointly owned with the Caledonian.

The First World War had a very damaging effect on the NBR because there were a lot of military establishments located in the operational area and it handled a considerable amount of heavy through traffic to the far north (especially for the Home Fleet based at Scapa Flow). Heavy usage of rolling stock and infrastructure coupled with lack of maintenance took a heavy toll. After the war, the promised reparations were not paid in a timely manner by the government and even though the company was totally impoverished. Eventually some monies were paid but only on the eve of the Grouping. This is one of the reasons why Gresley had to give some serious considerations to improving the Scottish locomotive stocks including the building of a number of the GCR-designed 4-4-0 D11 'Improved Directors'. The NBR chairman at this time was William Whitelaw and he took up the same position on the formation of the LNER.

Workshops

The original NBR workshops were situated at St Margaret's (Edinburgh). The Edinburgh, Perth & Dundee Railway's works were at Burntisland, (near the Forth) and the Edinburgh and Glasgow's works were at Cowlairs in the Springburn district of Glasgow. These latter named became the main NBR works.

Cowlairs was opened in 1842; this made them one of the oldest established works in the UK to remain open into the twentieth century. The last new engine to be built at Cowlairs was in 1924, thereafter, it was used for repairs and overhauls. It was closed in the 1960s.

Traffic

There was considerable passenger traffic in and around Edinburgh and Glasgow both suburban and long distance. Frequent services were run between the two cities. Coal was a major freight item especially around the Lothian and Fife coalfields. Fish, much of it destined for London, was carried from the East coast fishing ports and also from Mallaig. The NBR also had a share of servicing the heavy engineering works around Glasgow.

Waverley

Although this name is associated with Sir Walter Scott's novel of the same name and indeed many of his subsequent books were grouped under the title "The Waverley Novels", ironically, the name is English - the name of his eponymous hero.

When the NBR named its main Edinburgh station Waverley, (because it stood by the Waverley Bridge) it seemed to strike a chord, so the line to Carlisle was called the Waverley route (because it passed close to Abbotsford, Scott's home near Melrose) and many of its locomotives took names associated with the Waverley novels.

The name "Waverley" was used on several generations of locomotives and also on the NB paddle steamers (including the last Clyde steamer, which continues to exist in working order over 60 years after being built).

The LNER and BR perpetuated the theme, especially in the naming of Pacifics.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Richard Barron for the above information.

Thank you to Malcolm Peirson for the above pictures of the two Tay Bridges.

Thank you to Jim Pattison for the two photographs of the Ardlui section of the West Highland Line.