GNR: Kings Cross Station

Kings Cross Station was one of the most important stations on the LNER network. It is also arguably one of the most famous stations in Britain, if not the World. Built by the Great Northern Railway (GNR) as their London terminus, Kings Cross became the London terminus for the entire East Coast Main Line and a 'gateway to the north'. This is a status which it continues to enjoy, with classic Ivatt Atlantics and Gresley Pacifics replaced by Class 43 'HST' diesel electric locomotives and Class 91 electric locomotives.

History: GNR

The GNR reached London in 1850. The 'final push' was accelerated by the GNR Directors' desire to take advantage of traffic to and from the Great Exhibition of 1851. In order to open in time, a temporary station was built at Maiden Lane (now York Way). Officially named "The London Temporary Passenger Station", Maiden Lane open to passengers on 7th August 1850. The surroundings of the new station were not very auspicious, consisting of fields, industry (primarily brick), a Fever Hospital, and housing. The station does not appear to have been very substantial, but it did have a roof, and it survived long enough to be later used as a potato warehouse.

Shortly after the temporary station opened, on 24th October 1850 Lewis Cubitt presented his plans for a permanent station at Kings Cross. Lewis Cubitt reportedly described the temporary station as 'unsafe', and the Board accepted and approved his plans. By January 1852, reports requested by the Board describe the rate of construction as being satisfactory. Despite it being the most publically visible piece of GNR architecture, the Board was remarkably quiet and surprisingly unconcerned about the station's progress and imminent opening.

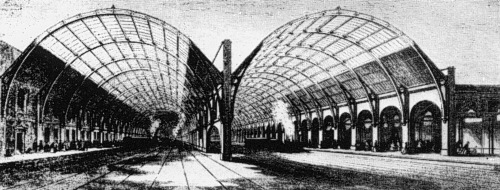

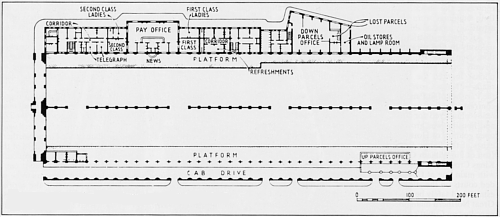

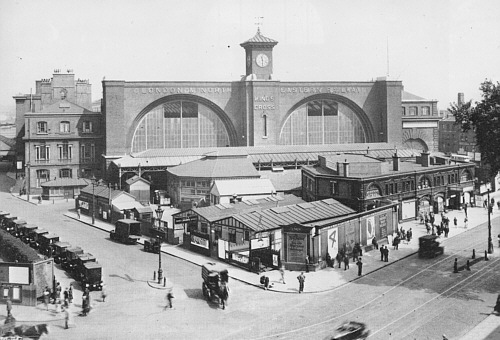

The 'Great Station' finally opened on 14th October 1852 and was quickly regarded as architecturally startling with a pair of yawning "train sheds". Although this shape has survived to the present day, the original construction used laminated timber beams according to the Wiebeking System, and not the girders familiar to us today. By modern standards, usage of this huge space was very inefficient. The station opened with just two platforms (against the east and west walls), and fourteen tracks. Attendant offices and passenger rooms were located on the west platform, which was used for departures. The east platform (aligned with York Way) handled arrivals only. Most of the tracks were used for storage and had no platform access. Small turntables and capstans allowed for rolling stock to be moved without the help of a locomotive.

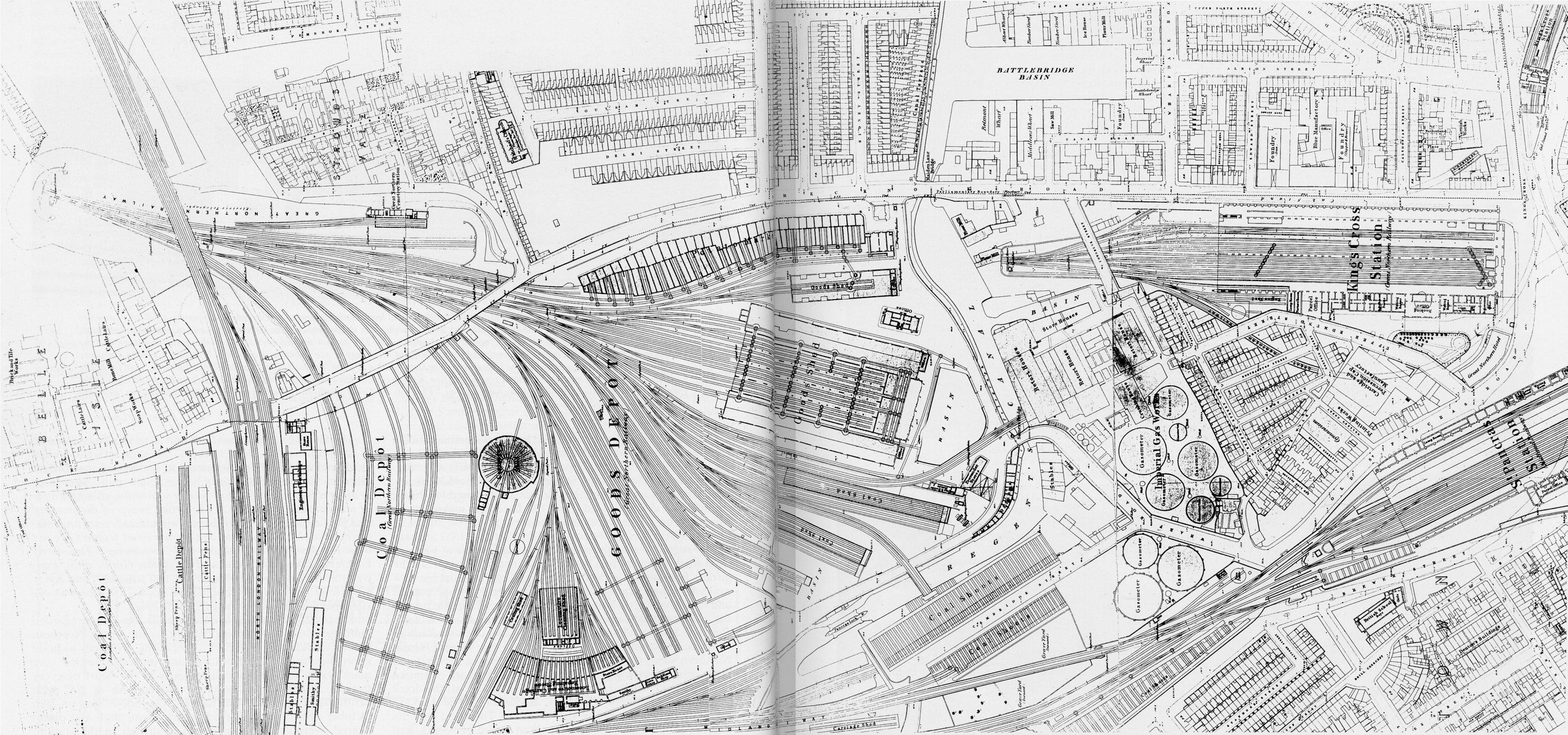

It only took a few years for this simple track layout to prove inadequate, when in 1858 the Midland Railway started to run services from Hitchin to Kings Cross. This was accompanied by continued growth in Great Northern traffic. During the 1860s, tunnels were bored connecting the GNR to the east-west Metropolitan Railway's Widened Lines. These included a platform on the 'Up' curve under York Way (closed in 1976). These tunnels now carry the Thameslink services.

Click for detailed map

The first 'commuter' station for local trains was opened in 1875 on the current location between the main station and the (then new) engine sheds. This was followed in the 1870s by the tunnelling of additional bores for the Gas Works and Copenhagen tunnels. These tunnels, north of Kings Cross have always restricted traffic movements between the stations, engine sheds, and freight yards; but the new bores doubled capacity and helped to relieve congestion. The relief was short lived and soon work was in hand to authorise a third double line bore for the Copenhagen Tunnel. This third bore opened in 1886, and it was followed by a third Gas Works Tunnel bore in 1892. 1892 saw another addition to the Kings Cross complex: the opening of the second departure platform in the main station. Amazingly, the west platform had served as the main station's only departure platform ever since opening in 1852.

Changes remained relatively subdued during the remainder of the GNR's existence. The suburban station was improved, and the curve to the Metropolitan Railway was made easier for locomotives.

Despite the grand facade, the location was criticised as a 'howling waste' and even the GNR's original Goods Manager, J. Medcalf, described the area as 'a long battalion of rag sorters and cinder beaters". Some have described that this turned into a kind of inferiority complex which was not helped by the construction of the ornate Gothic St Pancras Station next door. This general feeling may have contributed to the build up of small random buildings in-front of the Cubitt's famous facade. Despite promises to tidy what became known as the "African village", the recent re-modelling resulted in a front concourse building that continues to be out of place in-front of Cubitt's arches.

History: LNER

By the time of Grouping (1923), Kings Cross was still using separate platforms for arrivals and departures. This was a significant problem for suburban services where there was large amount of traffic which required quick turnarounds. Using different platforms introduced extra, unnecessary, shunting movements across the station. The solution required new signalling, but the result was a station approach which LNER Chief Engineer Mr Brown described as '[still] very complicated'. Many movements continued to be blocking movements, e.g. departures from platforms 1-5 would block all arrivals.

The signalling at Kings Cross became a Board issue in January 1930 when a major re-signalling project was approved. Much of the signalling equipment required frequent maintenance due to age. Rather than simply renewing equipment, the decision was made to switch to power signalling using an all-electric system and colour lighting. This would allow two signal boxes to be merged, and the signalling staff to be reduced from 13 men and 4 boys to 8 men and 3 boys. The re-signalling was performed in three stages, as each signal box's points and signals were converted in turn. The first stage (Belle Isle, north of Gasworks Tunnel) progressed without any hitches, but teething problems with the automated detection systems in the second stage (West Box) delayed the third stage (East Box).

Goods Traffic

Although Kings Cross is usually thought of as a major passenger station, it was also a major goods station for much of its existence. It is only in recent decades that the goods traffic has withered to virtually nothing. From the very beginning, the GNR's strength relied heavily on London's ever-growing requirement for coal, vegetables, and meat.

The size of the cattle market can be gauged by the size of the Metropolitan Cattle Market (later Caledonian Market) which opened in 1855 in the Copenhagen Fields area. The market included a prominent clock tower which still stands. Size estimates of the market vary with different sources quoting 30 acres and 74 acres. Weekly sales totalled about 25,000 sheep, 5000 oxen, plus calves, pigs, and other livestock.

The GNR carried huge amounts of coal from the Yorkshire-Nottinghamshire coal field to London. Coal drops appear to have been present at Kings Cross on the day it opened. By the late 19th century, Kings Cross had an extensive coal depot in the space between the Goods Depot and the North London Railway. Coal to Kings Cross would continue to be significant during LNER days where routing of slow coal trains amongst fast express services would become a major problem in of itself.

As already mentioned, Kings Cross had a large goods yard. Kings Cross was handling approximately a million tons of goods (excluding coal and cattle) by the end of the 19th century. Perhaps the most surprising component of this traffic was the huge quantity of potatoes handled by Kings Cross, and a significant potato market grew up on the eastern margin of the goods station alongside York Way. The potato market appears to date back to 1853 when the General Manager recommended a line of potato warehouses for the Goods Yard. Over time these warehouses grew. By 1920 there were 35-40 potato traders present. By 1930 the number of tenant potato traders had dropped to 28, but they were using a total of 39 warehouses. Each warehouse could hold between 2 and 4 open wagons. Potato traffic varied greatly with weather, seasons, and crop failures. During seasonal peaks, there could be a thousand loaded potato wagons in the Kings Cross area waiting to be unloaded.

Kings Cross Today

Modernisation during the 1960s saw the replacement of steam by diesel multiple units and diesel locomotives. During the 1960s and 1970s, the East Coast Main Line and Kings Cross were associated with the sight and sound of the powerful Deltics, which many enthusiasts saw (and continue to see) as worthy successors of the LNER Pacifics.

BR Managers first mooted the idea of electrification in the 1950s, but the first signs of electrification at Kings Cross would not appear until 1976 when overhead supports appeared at Gas Works Tunnel. This was a part of the electrification of inner suburban services, which were inaugurated in November 1976 with Class 313 electric multiple units (EMUs). Despite initial delays with Class 313 deliveries, the Kings Cross to Royston timetable was fully electrified by February 1978. 1978 was a significant year for Kings Cross operations as it saw the first use of 'High Speed Train' HST (later, Class 43) sets. Also, re-modelling and re-signalling resulted in the abandonment of the eastern bores of both the Copenhagen and Gas Works Tunnels. The remaining four lines through these tunnels were signalled for two way working.

Electrification of the East Coast Main Line itself finally started in 1985. The first section, from Kings Cross to Leeds, opened in 1988 with services hauled by newly built Class 91 ("Intercity 225") sets.

In today's post-privatisation world, Kings Cross sees a wide range of units in a wide range of liveries. Class 43 and Class 91 units continue to be common, but they are also joined by other types such as Class 180s; and Class 313s, 317s, 321s, and 365s on the local services.

Kings Cross in Film and on TV

King Cross has featured in a large number of films and TV programmes - far too many to list here. However it is most commonly associated with The Ladykillers (1955, Alec Guinness, Herbet Lom), and the Harry Potter series of films (2001 onwards, Daniel Radcliffe, Maggie Smith).

The stolen money in The Ladykillers is hidden as a parcel delivered on an N2-hauled train from Cambridge. The film features extensive scenes (and action) in and around the southern portal of Copenhagen tunnel. Mrs Wilberforce's house is clearly located above Copenhagen tunnel, although a house in the St Pancras area was used for the actual external camera shots of the house.

Harry Potter takes the Hogwarts Express from the magical "Platform 9 3/4". The real platforms 9 and 10 are located in the 'commuter' station on the west side, but J.K.Rowling intended it to be in the main (Cubitt-designed) station. The film locates the platform in this latter location.

Further Reading

- "The Great British Railway Station: Kings Cross", by Chris Hawkins, Irwell Press, 1990.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Eric Ramsay for the photograph of the Class 91s at Kings Cross in 2006.

Thank you to David Wainwright for the 1998 photograph of the front of Kings Cross station.